Migrants: “Come out, children, and brush your teeth”

Submitted by Danila Dugum on 21 August, 2013 - 23:27

http://www.colta.ru/docs/29793

Morning Visitors

The windows of the pricey Finnish supermarket Prisma, in Saint Petersburg’s former Warsaw Station, look out onto a structure with a half-collapsed roof and scruffy walls. People live there, however. They pay rent to the mysterious “proprietor” of the resettled residential building. He probably managed to “come to terms” with local “law enforcement” for a time, but the building is slated for demolition.

Early in the morning of August 13, uniformed OMON riot police and plainclothes officers raided the homes of migrant workers in this building on the city’s Obvodny Canal.

Human rights activist and sociologist Andrei Yakimov, from the Memorial Anti-Discrimination Center, recounts what happened.

“At around 6:30 a.m., the ‘police’ arrived—about nineteen uniformed men and five or six plainclothes officers. After the riot policemen kicked everyone out of the building (they were not stingy in dishing out insults and shoves, nor did they give pregnant women and mothers with infants any break), they checked everyone’s papers and began ransacking the rooms where people lived, breaking down doors and searching for valuables. The migrants claim that jewelry was pilfered, money was snatched from wallets, and video cameras, tablet computers and laptops were stolen: many of the workers were preparing to leave the country and had bought presents for loved ones in Uzbekistan. Some had taken out small loans to buy tickets home. A pregnant women had the ninety thousand rubles [approx. two thousand euros] she had borrowed for medical treatment (maternity ward expenses) confiscated. The riot policemen handed all these things over to the plainclothes officers, who loaded them into cars. The total loot came to about six large plastic bags. The uniformed thieves made several trips there and back to get everything.”

Three days before the pogrom, the Federal Migration Service and regular police had done a check at the building. After looking at their papers for the umpteenth time and warning the migrants that the building would be boarded up and all tenants must vacate it by August 20, the authorities had then left. They knew that most of the workers were soon returning to their homelands. The robbery thus appears to have been carried out with a suspicious punctuality.

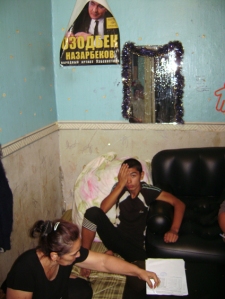

In the Building

Ibrahim, an Uzbek worker, meets me at the threshold of the house on the Obvodny. Limping, he leads me through a maze of dilapidated walls. In some places, oilcloth covers the leaks in the ceiling and the gaps in the windows. Surrounded by total poverty, people have managed to create some sort of living environment in several rooms. An elderly woman sits in one of these rooms: she is Ibrahim’s wife, Mavlyuda. Next to her is a pregnant woman, the one from whom police confiscated the money she had borrowed to give birth. Mavlyuda tells me that during the raid she lost everything she had earned. The riot policemen had told the plainclothes officers, “Go in and take what you want.” Not only did they steal rings, jewelry, money and new shoes, they even stole an unopened bottle of shampoo. (“What, they have no shampoo? And yet they stole it!”) A twelve-year-old boy had his new tracksuit confiscated. Police messed with the residents’ food supplies. They sprinkled laundry detergent into cooking pots, and tossed food out windows that they had smashed with the same pots. They poured cooking oil and flour onto rugs, clothes and beds. They took special pleasure in disposing of religious objects. Ibrahim holds a board in a broken frame—engraved verses from the Quran. Muslims hang such boards over the door. The riot policemen had trampled and spit on this board.

Ghalib, a construction worker from Uzbekistan, was beaten in the hallway of his refuge while attempting to prevent the robbery. Police confiscated his ticket home and tore it up in front of him. The women say that Ghalib is ashamed to tell where he was beaten. Police beat him in the kidneys and the groin so badly he urinated blood.

On the second floor, a girl of twelve or thirteen recounts how, first, stones were thrown at the windows, then men came and dragged the adults outside, saying to the children, “Come out, children, and brush your teeth.” Then the men began tossing televisions and household utensils out the windows.

His wife had warned Azamat, a truck driver, about the danger that day, and so he watched the pogrom from a hiding place. Later, he discovered that his money and a present (a watch) for his father, who has cancer, were missing. Azamat tells me how three of the policemen beat up a teenager whom he did not know. Non-Slavic in appearance, the boy did not live in the building (none of the residents had seen him before), he was just in the wrong place at the wrong time. “He got scared and ran, but they caught up with them and kicked him around like he was a football. When they picked him off the ground, he was limp like a rag,” Azamat says. He lifts a sweatshirt from a chair and shows me how the boy’s body fell.

After the pogrom, Pyotr Krasnov, a lawyer at the Memorial Anti-Discrimination Center, tried to help the victims.

“We filled out seven police complaint statements at the scene and left around sixty complaint forms in the resettled building in the hope that residents would submit them to the police precinct themselves. In the end, three of the seven people who filled out complaints came to the precinct with us, which I think is a huge success in itself,” says Krasnov.

Ghalib, the man who was beaten, took his complaint to the police. The first thing he was asked was, “Why do you live there?” He then sought medical attention. When the doctors found out it was the riot police who had beaten him, they refused to issue him any documents detailing his injuries.

“Illegals”: How Is That?

After conversing with the tenants of the abandoned building on Obvodny Canal, I got the impression they do not realize they inhabit the premises illegally, and that the “proprietor” to whom they pay rent has no real claim on this “residential space.” “My papers are in order” is the main code in a migrant’s life, and the residents of the building on the Obvodny repeat it like a mantra. Their lives are lived outside the law, and even outside any notion that somewhere it exists and functions. The migrants, especially the young people, believe that buying the necessary documents (it doesn’t matter where) is in fact the correct, legal way of doing things. Many are surprised to learn that a “work permit” that has to be purchased is a fake.

Pyotr Prinyov, from the trade union Novoprof, opens a newspaper and reads a want ad aloud.

“Look here. ‘Wanted: Uzbek nationals with work permits . . .’ But it is the employer who is required to obtain a work permit. That is, it is issued with the employer’s involvement. But if someone shows up with a readymade work permit, then it is 99% certain it has been purchased. There are tons of want ads like this. It is clear that employers are at fault, and that migrant workers are forced to play by these rules.”

But people in the house on the Obvodny do not understand this. It was only the robbery that angered the residents. Document checks and arrests are routine. Regular extortions by police on the streets, and getting ripped off at hard jobs with long hours are things to be endured for the sake of families. But where is the reward now?

We talk with another woman, whose husband is being deported. With tears in her eyes, she speaks about three children in Uzbekistan, how they will have to go back, and that her husband will be unable to re-enter the Russian Federation for five years. At one point, she says something that applies not only to herself.

“Tell the Russians we are honest workers. Tell them we aren’t criminals. My boss at the kitchen [where she works], a Russian woman, almost started crying with me when she found out I was leaving: ‘Where will I find someone like you?’ She’s satisfied with me! Why do you say on television that an Uzbek killed someone? We’re not all like that. Tell them that Uzbeks are honest workers. We’ll leave, but will a Russian woman go clean the streets and stairwells like we do?”

Contrary to the popular myth of the total criminality of migrants, according to official statistics from the Prosecutor General’s Office (a body that checks the police and thus has no interest in fudging the numbers), the majority of crimes are committed not by migrants and guest workers, but by Russian citizens (22.57% versus 77.43%). And Moscow’s judicial department informs us that, in 2012, immigrants from the Commonwealth of Independent States (i.e., the former Soviet republics) had 17% of the crimes committed in the city on their conscience, but a quarter of these involved faked migration papers and work permits.

Andrei Yakimov debunks another myth.

“In fact, most of the migrants in Russia would like to forget they are migrants. They would adapt quite quickly were they allowed to. The older generation remembers the Soviet Union as a golden age, when they had it all. The younger generation of immigrants believes that dissolving into Russian society is better than going home. And that fabled Islamic solidarity is actually a fiction. Look at the mood in Tatarstan: Tatars experience the same xenophobia towards immigrants as Russians do.”

For now, though, everything goes on as before and will continue to go on this way. According to Memorial’s calculations, a so-called native Petersburg is twenty-six times less likely to fall victim to police violence than a person of “non-Slavic” appearance.

As you leave these robbed and humiliated people in their ruined shelter, you inadvertently catch myself thinking about what Alexander Herzen once said about the pacification of Poland: “I am ashamed to be Russian.”

Photos © Memorial Anti-Discrimination Center

http://therussianreader.wordpress.com/2013/08/21/anti-immigrant-pogrom/